• Logbook

• Road Stars

Photo album:

• Cordillera de los Frailes

• Maragua festival

Download GPS files for La Cordillera de los Frailes:

• GPS track & waypoints

This stage goes from Potosi to Sucre, but instead of following the paved road, we take a detour through the Cordillera de los Frailes. Someone told us this is one of the steepest areas of the country, but we want to see how farming communities live in the highlands. During the trip we pass through villages of only a handful of houses, some of which are already abandoned. In this zone the predominant language is Quechua, and although most people speak Castilian, we have met shepherds who don´t understand it. One thing that amazes us is how they can grow wheat, potatoes or anything on these brutally steep slopes where their fields are located. Sure, there aren´t too many flat areas, but it seems that potatoes would tumble downhill even before being harvested. The whole region is between 11000 and 14000 feet high. Despite this, the winter does not seem too crude, or at least this winter. At higher elevations the temperature drops below freezing at night, but during the day the sun heats up nicely and the skies are rarely covered by clouds. Very unlike the warnings we have received both in Potosí and Sucre about the unfriendly character of its inhabitants, these people are very kind and we have always been welcome with a smile everywhere. We've also been lucky enough to coincide with the farmers´ festivity, when they forget the harshness of every day's life and dress up to spend 2 days dancing and drinking chicha until they drop drunk and exhausted. These are our experiences in the Cordillera de los Frailes.

Stage index:

July 20, 2011: From Potosí to nowhere (Profile)

July 21, 2011: From nowhere to Cienaguilla (Profile)

July 22, 2011: From Cienaguilla to Tinguipaya (Profile)

July 23, 2011: From Tinguipaya to Cienagoma (Profile)

July 24, 2011: From Cienagoma to (Colque) Maragua (Profile)

July 25, 2011: Colquemaragua festival

July 26, 2011: From Colquemaragua to Chaunaca (Profile)

July 27, 2011: From Chaunaca to Quila Quila (Profile)

July 28, 2011: From Quila Quila to Sucre (Profile)

Profile for the entire stage:

July 20, 2011: From Potosí to nowhere

Unlike other cities, leaving Potosi is quite easy. Traffic on Highway 1, which goes to La Paz, is very light. Even the streets leading to it are not too crowded. The only unpleasant moment is when we make the mistake of stopping behind one of the microbuses. Even with the exhaust pipe going almost up to the roof, the cloud of black smoke when they start moving is such that you are engulfed by it. On top of this, since we are at 13000 feet, you can only hold your breath for a few seconds. Inevitably you end up inhaling some of the smoke, but only once, for the lesson is quickly learned.

We are surprised that the road is still paved and it continues so until Miraflores. Between the 2 villages we pass the Eye of the Inca thermal baths. When we get to Miraflores, we make sure we take the right direction to Mondragón. The pavement ends, but instead of a dirt track, we find a road paved with cobblestones that will take us to Mondragón. Arriving at this town we can see a canyon in the distance where the river we follow escapes through. At the entrance of Mondragón we find a small store and stop to buy more water. The old woman who takes care of us is super friendly and asks us where we are going. We tell her to Tinguipaya and she replies that we missed the turn off, we must go back and take a track that goes up. Good thing she was curious.

At mile 21 we reach a pass and stop to have lunch. From here we descend gently to a junction that goes to Moropoto, a tiny village that looks abandoned. We pass the turn and continue towards Tinguipaya, our destination for today. Until now we are following the route we drew yesterday on the maps we got from the IGM (Military Geographic Institute) in Sucre and Potosi. In both offices they helped us enormously to get maps that cover this area. They warned us they are old (from the 70’s) and are not updated, but these are the only ones we know exist.

Farther ahead we find a junction that is not on the map. We would take the right fork, but is in terrible condition, covered with bushes and impassable to vehicles. However, the left one does not follow our direction. We explore on foot the left fork, up to a vantage point and definitely it’s not going where we are headed. In addition, the direction of the power line in sight confirms our decision. So we push the bikes to overcome the non cyclable section and descend to cross a dry riverbed. We push the bikes again uphill trying to avoid the thorny bushes that have grown on the road. We are sure we are going to have a flat because it is impossible to avoid them all. In some of the climbs Judit gets too far behind. In the roughest climbs we have to push again and occasionally I go back to help her to push her bike. Before a couple of miles we realize that her rear wheel is losing air. We knew it. Judit is strangely tired and her throat is sore, so she sits down as I begin to replace the tube. She doesn’t feel well and although it’s sunny, she begins to get cold, so we decide to pitch the tent right here and wait to see how she feels tomorrow. Once inside the tent, she has chills and looks for the thermometer in our first aid kit. Indeed, as she suspected, her temperature is higher than normal. She changes clothes, takes a couple of antipyretic and anti-inflammatory pills and gets into the sleeping bag. I adjust the disk brake to avoid the dragging after removing the wheel and while she rests, I walk up the road to see where it leads. We find it very strange that this road is so overgrown. Supposedly we are on the main road in the area. Perhaps they have built an alternative one easier to maintain. I climb a small hill from which I have a good view. From here I see that our road joins another track in good condition. It seems that the theory of the alternative road could be confirmed. I go back to the tent and prepare a tea for Judit who is unusually tired. The air is very dry and despite the 2 two-liter bottles we bought in Mondragón, we have only some left, so we decide to have something that doesn’t require water for dinner. Our dinners usually consist of soup or pasta, but today we are having cereals. Gradually Judit is feeling better, but the fever doesn’t go down.

Although we are at 11500 feet, it’s not too cold. From inside the tent we notice the moon light shining brightly outside. Of course, this doesn’t prevent us from falling asleep instantly. Tomorrow we will decide how to proceed.

July 21, 2011: From nowhere to Cienaguilla

We start to stretch when the sun begins to heat the tent. Judit is feeling better but her throat still hurts when swallowing. The decision is to proceed ahead with the initial route. Instead of the usual cereal with milk, today we eat the cookies we bought at the convent of Santa Teresa in Potosí. These are a kind of pastries a little rough to swallow but we want to conserve water until we can recharge.

We follow the road full of thorny bushes to get to the track I saw yesterday from the top and take it in the direction it seems correct to us. A couple of miles ahead we see a shepherd at the foot of the mountain and stop to ask her. We have been warned that the residents of this area are wary of strangers. They fear they may come to take away their lands or force them to move out. We see that the shepherd leans over to pick up a stone and places it in her sling. Fortunately it´s to control the herd of goats she guides. Judit, despite her tiredness offers to go down to ask her about the road. We think the shepherd will feel less fearful talking to a woman, even if she has red hair. From the track I see the two of them making gestures and pointing to where the road continues. Finally they shake hands and Judit begins to climb back up the hill to where I am. When she arrives, she says panting: "she only speaks Quechua, I have not understood a word". Great. We have been warned about that too. I look down and see that the shepherd starts to run towards us. She leans over again to pick up some stones and unrolls her sling. This time she is coming for us. But no, the herd was approaching the road and she throws a few stones to make the goats come back down. Judit, even not understanding a word, found her very friendly.

We decide to resume and go ahead. The track continues to go downhill and at the bottom we see a canyon with vertical walls, which scares us. After a curve, Isla, another tiny village, appears in sight and we stop to ask again. This time it's my turn. Of the 20 houses we only see a couple of people, busy in their courtyard. Luckily this time the old man speaks Castilian. He tells me that we are indeed in the old road to Tinguipaya, but nowadays “you can only make it on foot, it´s not feasible for motorbikes". The bridge over the Pilcomayo River partially collapsed years ago and you can only cross it on foot, clutching to the structure that remains standing. "The bridge is 70 feet from the water. If you fall, bye bye. The water will take you away". In addition, across the bridge, the road is abandoned and full of thorns. It takes me 3 attempts to make him understand that we are on bicycles, not motorcycles. When he finally understands then it seems more plausible, so I draw a map in the sandy soil using a stone. He must think I'm stupid using a stone, when the finger is a much better tool and he adds some details to the map. After talking a bit more he seems to think it´s not a crazy idea to cross with the bikes so I finish the conversation and ask for water. He offers to take it from a bucket connected to a hose. The water is clear but I ask him where it comes from since they warned us that water from the Pilcomayo river is polluted with mercury and he just said that the destroyed bridge is to cross the Pilcomayo. "No, no, this is from up there, not from the river". When we shake hands and turn my back to leave, he says, "But you will suffer if you go that way. You should go back to Totora D on Highway 1 and take the other road to Tinguipaya”. Puf. The truth is that even speaking Castilian it’s difficult to communicate. In addition to speaking like Master Yoda from Star Wars, putting the verb at the end of the sentence, they say one thing and after a while the opposite. I go back to the road where Judit sat a while ago, tired of waiting. I repeat the misleading information and we decide to keep going. A few yards ahead see 2 more people. They look younger and perhaps we can communicate better with them. In addition, it will be a second opinion. The father speaks Castilian and he is more or less consistent with the old man, but with more emphasis on to turn back to Totora D. This time the map on the sand is in 3D and he describes how the road overcomes the vertical walls of the canyon. Back on the road again, this time we decide to follow locals’ advice and return to the asphalt through the road they told us, rather than face the broken bridge and thorns.

After a little more climb we get to a pass from where the track drops to Totora D. Judit is feeling exhausted and we postpone the decision to where to continue to until we reach the pavement. Once there we buy water and analyze the options. We finally decide to stick to the plan to tour the Cordillera de los Frailes. Judit is too tired to keep riding today, so we ask for accommodation in Totora D, but there is none. We get on a bus that takes us to Cienaguilla, near where the track to Tinguipaya begins. According to the driver in Cienaguilla we will find accommodation. We stop in front of the place and there is no vacancy. The other “hotel” in the village is under construction, but we managed to convince the owner to let us put the tent in an empty room on the top story and there we settle. We have dinner at the restaurant: rice soup with French fries on it and ají de carne, a kind of spicy stew with rice and andean potatoes. The kitchen is visible and I get close to see what the ají de carne is. From now on we have to reduce our cleanness requirements: here in Bolivia, at least in the villages, food is served with their hands.

July 22, 2011: From Cienaguilla to Tinguipaya

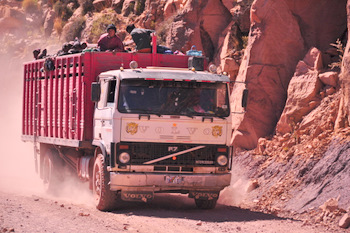

At 6:40 the owner starts yelling from the restaurant below and awakes us. We assume it´s to wake up the girls who work at the restaurant, but we start to get going. At 9:00, an hour earlier than usual, we're pedaling. By that time, the girls are preparing breakfast for the human cargo of the truck just parked at the door.

After passing the main mountain pass of today we find a half-frozen lake. It's fun to see how a group of ducks tries hard to get around. At times they swim, sometimes they walk on the ice and occasionally they break it and sink. The best part is to see them land on the ice, sliding a long way to end up stopping successfully or falling in the water.

July 23, 2011: From Tinguipaya to Cienagoma

Behind each curve there is another one for miles and miles uphill. Around mile 17 and after climbing 3600 feet, although it´s only 4:00PM, we're thinking about camping and continue to Maragua tomorrow. We are in one of the tiny villages that we have been passing by and Judit asks a shepherd if we can camp somewhere. She understands Castilian but only speaks Quechua, so there is no exchange of information. At that very moment, a young guy shows up walking in the same direction we are going. We ask him and he tells us that just around the curve we see on the horizon is Cienagoma, a larger village where we will find lodging. He is heading towards it and resumes his way briskly while we get on the bikes. After a few curves we pass him and he again states this is the last curve. After this, it's all downhill to Cienagoma. When we are still a few yards from him he asks if we can take him. At this point the slope is gentle and it seems that the distance is short, so I tell him to seat on my saddle and I’ll pedal standing. We don’t know yet, but there are at least 1 more mile up and 1.5 down from Cienagoma! I have to stop a couple of times to rest while going up. During the descent he is the one asking me to stop. With the bumps he is slipping forward and I guess the tip of the saddle is hurting his sensitive parts. When we finally get to Cienagoma Judit thinks he is limping as he heads toward the houses. In fact, he puts his hands in his pockets to clearly relocate things.

The village has less than 20 houses but the school is brand new and has a sports court. We ask if we can sleep in the school building but it´s closed and the principal doesn’t return until Sunday morning. However, we are allowed to put up the tent on the sports court. By now we have a group of curious children around us who will follow us everywhere. We go to the sports court and see that some of the classroom windows are broken. We sneak through one of them and settle on an empty class. We take advantage of the last moments of sun to clean the chain, covered with dust for the last 4 days, under the close supervision of the kids. When we put up the tent they watch us with their eyes wide open. One of them attempts to enter the classroom and we have to stop him. Of course, when we get into the tent, they do all kinds of mischiefs like knocking on doors and windows and run away immediately while laughing. We don’t care too much. We know that when the sun goes down at 13500 feet is too cold outside to go around doing such things. When we brush our teeth before going to bed, we have an opportunity to enjoy the incredibly starry sky. The Milky Way is amazing here.

July 24, 2011: From Cienagoma to (Colque) Maragua

The climb of the second pass is in general acceptable, but Judit still has that sore throat and if she stops taking the antipyretic pills, the fever appears again, so we take it easy. After overcoming it, we descend about 650 feet and start the third and final pass of the day. To get to the top we just have to climb 150 feet, but it seems like 1500. At this elevation, the effort is multiplied. Almost reaching the summit, we catch up with a peasant leading his 4 donkeys loaded with sacks. We talk to him a few minutes and learn that he is heading, like us, to Maragua to sell their goods. The donkeys are loaded with chuña potatoes, one of the types of Andean potatoes grown in the area. They have the peculiarity that once harvested, they are dried in the sun and frozen at night for a few days. They also carry dried meat. It turns out that tomorrow there is a celebration in Maragua, so there will be a ton of people and that always means business. For him, the business can start right now, and he tries to sell everything to us, from potatoes and meat to his own hat.

The downhill to Maragua is continuous, almost 1600 feet in 5.6 mi. It´s only interrupted by several dogs that come to us barking fiercely, but they already know what a stone is. When we stop and lean over to pick up a couple of stones, they stop barking. If we threaten them to throw the stones, they turn around and disappear. Some are stubborn and we have to actually throw the stones to scare them away. Halfway down we stop to have lunch and enjoy the views of the valley we will follow towards Potolo. On the other side of the valley we can see the climb towards Ocurí, but luckily it’s not for us.

Once in Maragua we find a shop run by a couple of very nice and lively elderly to replenish water. They tell us that tomorrow starts the village festivity, a bunch of people will come in groups wearing traditional costumes, dancing to the sound of the charango, etc., etc. They finally convince us to stay. At first we were reluctant to stay because these parties include fights among participants from rival villages with some degree of violence that in some cases even ends up with the death of one of the participants. As they say, if there is a good fight, it’s a good party... Alcohol is drunk in quantity, which always creates conflicts. But we are told the dances are in the morning and men do not start drinking until the evening, so our plan is to stay and leave around noon. The next step is to find accommodation. The store owners tell us that next to the church there is a small room where we could spend the night, but one have to ask permission to the mayor. Just then the mayor passes by riding his motorcycle. The old man gets up quickly calling him and gets his attention. No problem, we can stay there. Now we have to find Atanasio, the person who has the keys. The plan for this is to sit back again in the doorway of the store, just where we were before the mayor showed up and wait for Atanasio to pass by. During the next two hours we talk about the party, the Copa America tournament, tourists who pass through town... We finally figure out the mystery between the two Maraguas in the area. We are now in Colque-Maragua (Colque means silver in Quechua). The

Maragua related to the crater we will visit in a few days is called Trigo-Maragua, due to the wheat fields.

The main street is lined up with stalls selling all sorts of products: food, charangos and decorations for tomorrow’s costumes. At all times people are going back and forth, so we are entertained. Although one might think these seniors just let time pass, the reality is that they don’t miss any detail of what is happening: the mobility from Sucre or Potosi, who passes by and where they go, the pair of gringo backpackers who just arrived, and so on. Finally Atanasio shows up. The old man calls him but he is too busy to talk about it now and will come back later.

We settle in the room next to Gustavo’s and after a snack, Judit lies on the only bed in the room. I, from the sleeping mat on the floor, use the time to write up today’s experiences as the band of the village incessantly repeats the same tune in the plaza. The party has begun. Occasionally they throw fireworks and firecrackers, but even all that rumble cannot wake Judit up.

July 25, 2011: Colquemaragua festival

Today is the big day for the farmers around Maragua. They left their villages and communities very early in the morning towards Maragua. Yesterday they told us that after 9 AM the first groups of dancers start arriving, so at that time we are in the plaza waiting. The main street is quiet. Vendors are still putting together their stalls, store owners take out boxes and tables to the sidewalk to show their products better. At 10 everything is more or less the same. At 11 no group has showed up yet. In theory, at this time begins the religious celebration in the church. As we need to coordinate with Gustavo for the single key to the residence of the parish, we go back to talk to him. The Mass will also be delayed. The farmers should still be on their way.

The rhythm of the music is very repetitive and is marked by the dancers’ footsteps running synchronously. The charangos and flutes are the only instruments used. The lyrics of the songs are in Quechua and although we don’t understand a word, we almost dare to say that are always the same. The groups advance from the entrance of Maragua where they come from their communities to the plaza, occupying the entire width of the street. In front of the church they form a circle with the charangos in the center. Every few stanzas they stop turning and perform a strong footwork. Then, they turn again, this time in the opposite direction and repeat. If the space in front of the church is occupied by another group, they align in a row and wind across the plaza between the other dancers.

July 26, 2011: From Colquemaragua to Chaunaca

Long before 7 AM we hear the same tune that was been played all day yesterday. It turns out that yes, they have been dancing and playing all night. We poke our heads into the street and indeed, some groups are still repeating the same dance as yesterday, less vigorously and with fewer participants though. We guess some have fallen in combat and are still sleeping drunk.

Now we follow a different river, but still downstream. However, after a while it flows through a gorge and we have to climb up and then down to go around it. This is the last significant climb of the day. On the other side, with good views over the canyon, we are rapidly approaching Chaunaca. We cross the Ravelo river and we have only one last ramp to the village. Chaunaca's population is only about 50 people, but we find lodging with hot shower. After 7 days without showering (not because we are afraid of cold water, but because there was no shower in any of the places where we slept), it is a pleasure and reminds us how well accustomed we are to certain common things that elsewhere are a luxury.

July 27, 2011: From Chaunaca to Quila Quila

The cereals we bought yesterday in one of the two stores in Chaunaca are a fiasco for a breakfast. Yesterday we gobbled up one of the bags when we settled. For that, the popcorn-flavored chocolate was acceptable. But today, when we dip them in milk they become a lumpy mass that slips on the spoon and is difficult to swallow. Perhaps it’s the reaction with the milk powder. In the end, the best solution is to eat them without dipping. The worst thing is that we bought 3 bags...

We leave Chaunaca and pedal down directly to the river. There is no bridge to cross and Judit, the smart one of the couple, removes the bags and walks her bike through the huge stones arranged for this purpose. I, the macho, cross the river riding and, having miscalculated the depth of the water, get my feet wet up to the ankles. Just today I put clean socks after yesterday’s shower...

The climb across the river is only 700 feet up, but in less than 1.5 mi and we have to stop several times to rest. Judit, who is slowly recovering from her cold, now feels better and goes up ok except for some coughing. Then we go down to a revine to climb back up the hill that leads to the plateau where Trigo-Maragua, or simply Maragua is. This road is relatively new and certainly not on our IGM map. Although the track only has a couple of years, the terrain is not in good condition. Rocks, sand and gravel makes it difficult to progress faster. According to the Lonely Planet guide book, the view of the Maragua crater is one of the most amazing panoramas is Bolivia. Well, it’s good but not that spectacular. The rocks of the flat area are purple and the strata of the Serranía de Maragua to the south, forms some chained curious arches. In the center of the depression there is a small hill where the cemetery is located. We ask at the village how to get to the Talula hot springs. According to our map, there is a trail but a couple of locals do not recommend it for cycling. They advise using the new track leading to Quila Quila and then take the road to Talula. After the experience during the first 2 days of this stage, we decide to follow their advice and head to Quila Quila. To get there, means climbing the Serranía and that means more rocks and sand. On top of that, today is much warmer than any other day and the sweat runs down our faces. From the summit we can see the church of Quila Quila and we rush down the hill.

July 28, 2011: From Quila Quila to Sucre

After a few miles we go back down now with Sucre in sight. We ride through a degraded suburb with rubbish everywhere. For the amount of children in uniform walking toward the city, it must be time to return to school. It couldn´t be otherwise, to get to the center of the city, we have to climb. At least there is little traffic and it’s not stressing. Finally we settle in a hotel one block from the central plaza and we take an infinite shower after 9 days in the Cordillera de los Frailes. We wanted to see the life of the peasants of the highlands and the tour has given us a good idea of the tough life they live. Severe weather, the continuous ups and downs of the terrain, water scarcity and isolation make this region an inhospitable area. Yet they still grow their potatoes and wheat as did their grandparents and probably their grandparents' grandparents. Having been spectators of their party at Maragua has been a plus we didn´t count on. Despite the hard and spartan life they have, there is no shortage of desire or strength to walk a few hours to reconnect with friends, to dance, play music and drink beer non-stop for a couple of days.